Eculizumab, concentrated solution for I.V. infusion, 300 mg in 30 mL, Soliris® - March 2014

PDF printable version of this page

Public Summary Document

Product: Eculizumab, concentrated solution for I.V. infusion, 300 mg in 30 mL, Soliris®

Sponsor: Alexion Pharmaceuticals Australasia Pty Ltd

Date of PBAC Consideration: March 2014

1. Purpose of Application

The re-submission requested listing in Section 100 (Highly Specialised Drugs Program) or inclusion on the Life Saving Drugs Program for the treatment of atypical Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome (aHUS).

Highly Specialised Drugs Program:

Highly Specialised Drugs are medicines for the treatment of chronic conditions, which, because of their clinical use or other special features, are restricted to supply to public and private hospitals having access to appropriate specialist facilities.

Life Saving Drugs Program:

Through the Life Saving Drugs Program (LSDP), the Australian Government provides subsidised access, for eligible patients, to expensive and potentially life saving drugs for very rare life-threatening conditions.

Before a drug is made available on the LSDP it must generally be accepted by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee as clinically necessary and effective, but not recommended for inclusion on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme due to unacceptable cost-effectiveness

2. Background

Eculizumab is currently available through the LSDP for the treatment of eligible patients with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria.

This was the second submission requesting that eculizumab be listed in Section 100 (Highly Specialised Drugs Program) or included on the LSDP for treatment of aHUS. The first submission was not recommended for listing on the PBS at the March 2013 PBAC meeting on the basis of uncertain clinical effectiveness and unacceptable cost effectiveness.

3. Registration Status

Eculizumab was designated an orphan drug and approved by the TGA for the treatment of patients with aHUS on 3 October 2012. Eculizumab is currently TGA registered for the following indications:

- For the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) to reduce haemolysis.

- Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (aHUS).

4. Listing Requested and PBAC’s View

Section 100 (Highly Specialised Drugs Program)

Authority required

No specific wording proposed.

OR

Life Saving Drugs Program Funding eculizumab under the Life Savings Drug Program is restricted for use in patients with atypical haemolytic syndrome with a confirmed ADAMTS-13 activity of >5% and where Shiga-toxin producing E coli (STEC) infection has been ruled out and are either:

- Patients with active evidence of progressing thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) who have not progressed to chronic end stage renal disease (ESRD) (greater than four months); OR

- Existing patients who are on chronic dialysis demonstrating extra-renal TMA;

AND

- Existing patients who are on chronic dialysis and are suitable for a kidney transplant.

The PBAC noted that no specific wording was proposed in the submission for a Section 100 (Highly Specialised Drugs Program) restriction. The restriction will need to be finalised in consultation with the sponsor, the Department of Human Services and the Restrictions Working Group.

The PBAC noted the view of the clinical expert at the hearing that the threshold for ADAMTS-13 activity to diagnose aHUS was somewhat arbitrary, and that >10% is generally used in Australia. The PBAC noted that a cut-off of >5% is proposed in the restriction and that the four eculizumab studies presented in the submission used >5% as the threshold for diagnosis of aHUS, while the Australian registries used >10%. The PBAC considered that it was unclear whether the spectrum of disease is different between these two thresholds, but concluded that the more conservative cut-off of >10% was more appropriate.

The PBAC noted that the requested eligibility criteria appeared to restrict use in existing patients who are on chronic dialysis to those patients who both:

- demonstrated extra-renal TMA, AND

- are suitable for a kidney transplant.

The PBAC noted that the treatment algorithm proposed in the submission defined the chronic dialysis group as “patients receiving chronic dialysis (greater than four months) and requiring transplant or experiencing extra renal TMA”. Thus the PBAC considered that the requested eligibility criteria may have intended to restrict use in existing patients who are on chronic dialysis to those patients who either:

- demonstrated extra-renal TMA, OR

- are suitable for a kidney transplant.

Listing was requested on the basis of a cost-utility analysis compared to best supportive care.

5. Clinical Place for the Proposed Therapy

aHUS is a chronic, rare, progressive condition that causes severe inflammation of blood vessels and the formation of blood clots in small blood vessels throughout the body, a process known as systemic thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). TMA causes end organ ischaemia and infarction and in aHUS most commonly affects renal function. A genetic basis for the disease can only be established in some patients, and some, but not all, patients experience recurrent episodes.

The PBAC considered aHUS to be a severe disease, associated with high risk of end stage renal failure and mortality, particularly at its first presentation. The PBAC considered that there is a high clinical need for an effective treatment for aHUS, particularly acute events.

The PBAC noted that the submission estimated that the prevalence of aHUS is 3.3 to 7 cases per million.

The re-submission proposed two algorithms to define the eligible patient populations who have a confirmed diagnosis of aHUS (based on ADAMTS-13 and STEC infection being ruled out) and who have:

1. Active and progressing TMA in the hospital setting; and

2. Patients receiving chronic dialysis (greater than four months) and requiring transplant or experiencing extra renal TMA.

The PBAC considered that the two clinical management algorithms proposed in the re-submission defined the eligible patient populations more clearly than those provided in the previous submission.

The PBAC considered that the two clinical treatment algorithms proposed are reasonable based on the current clinical understanding of aHUS. The PBAC noted that clinical knowledge regarding aHUS is evolving, and that this evolution will dictate future clinical algorithms.

The PBAC considered that there are a number of uncertainties regarding the diagnosis of aHUS, including the role of genetic testing, the positive and negative predictive values for the tests for ADAMTS-13 and STEC, and whether the spectrum of disease is different between the thresholds for ADAMTS-13 activity of >5% and >10%.

6. Comparator

The re-submission nominated supportive care consisting of plasma exchange/infusion, dialysis and/or renal transplant as the main comparator. This was the same as the comparator nominated in the previous submission.

The PBAC considered that supportive care is an appropriate comparator, and noted that the type of supportive care will vary depending on the stage of aHUS.

7. Clinical Trials

The re-submission was based on four studies of eculizumab, two of which had been previously considered by the PBAC (studies C08-002, n=17 and C08-003, n=20), and two of which had not (C10-003, n = 22 and C10-004, n = 41). The two new studies provided data on an additional 63 patients.

Chronic dialysis was an exclusion criterion in three of the four eculizumab studies (C10-003, C10-004 and C08-002). One of the studies was conducted in paediatric patients (C10-003), one in adult patients (C10-004) and the other two were in a mixture of adult and adolescent patients (C08-002 and C08-003).

The four studies of eculizumab were single arm, open-label, non-randomised, prospective studies. The risk of bias in these studies was high.

The PBAC considered that there was significant heterogeneity between the eculizumab studies, which included patients with different baseline characteristics, at different stages of disease (first episode, recurrent and transplant) and with different pathogenesis (genetic abnormalities, auto-antibodies and unexplained).

The re-submission presented nine observational studies of supportive care in aHUS, and relied on two for its overall survival comparison (Coppo 2010 and Kremer-Hovinga 2010; the latter had been considered by PBAC before). The PBAC considered that two further observational studies (Noris 2010 and Fremeaux-Bacchi 2013) and the Australian TMA registry were informative in helping to determine the natural history of aHUS.

The observational studies of supportive care were single arm, observational, non-randomised studies. The PBAC considered that the risk of bias in these studies was high.

Publication details for the relevant studies are presented in the following table. Publications not presented in the March 2013 submission are shown in italics.

|

Trial ID |

Protocol title/Publication title |

Publication citation |

|---|---|---|

|

Eculizumab studies |

||

|

C08-002 |

Clinical Study Report C08-002 A/B: Eculizumab (Soliris) C08-002A/B an Open-label, Multi-center Controlled Clinical Trial of Eculizumab in Adult/Adolescent Patients with Plasma Therapy-Resistant Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS)

Eculizumab efficacy in AHUS pts with progressing TMA, with or without prior renal transplant.” |

Legendre et al 2013 NEJM. 368(23), 2169-2181.

|

|

C08-003 |

Clinical Study Report C08-003A/B: An Open-Label, Multi-Centre Controlled Clinical Trial of Eculizumab in Adult/Adolescent Patients with Plasma therapy-Sensitive Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS)

Hematologic and renal improvements in atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome patients with long disease duration and chronic kidney disease in response to eculizumab.

Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical haemolytic-uremic syndrome. (C08-002 and C08-003) |

Legendre et al 2013 NEJM. 368(23), 2169-2181.

Licht et al 2013 (a) Pediatric Nephrology 28 (8): 1565-1566.

Legendre et al 2012(d) N Engl J Med 368(23): 2169-2181 |

|

C10-003 |

Interim Clinical Study Report C10-003: An open-label, multi-center clinical trial of eculizumab in pediatric patients with Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS) |

Greenbaum et al 2013. |

|

C10-004

|

Interim Clinical Study Report C10-004: An open-label, multi-center clinical trial of eculizumab in adult patients with Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS) |

Fakhouri et al 2013 (d); ASN abstract |

|

Supportive care studies |

||

|

Noris 2010 |

Relative Role of Genetic Complement Abnormalities in Sporadic and Familial aHUS and Their Impact on Clinical Phenotype. |

Noris et al 2010 Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology 5:doi:10.2215/CJN.02210310 |

|

Kremer Hovinga 2010 |

Survival and relapse in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. |

Kremer Hovinga et al 2010. Blood 115(8): 1500-1511. |

|

Fremeaux-Bacchi 2013 |

Genetics and outcome of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: A nationwide French series comparing children and adults. |

Fremeaux-Bacchi et al 2013. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 8(4): 554-562. |

|

Coppo 2010 |

Predictive Features of Severe Acquired ADAMTS13 Deficiency in Idiopathic Thrombotic Microangiopathies: The French TMA Reference Center Experience. |

Coppo et al 2010. PLoS 5, (4) e10208. |

The key features of the studies are presented in the table below.

|

Trial |

N |

Design/ duration |

Patient population |

Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eculizumab studies |

||||

|

C08-002 |

17 |

Prospective single arm; follow up ranged from 0.5 to 3.5 years |

Adult aHUS |

- Haematologic normalisation - TMA response - CKD improvement (eGFR) - HRQoL change |

|

C08-003 |

20 |

Adult & adolescent aHUS |

||

|

C10-003 |

22 |

Paediatric aHUS |

||

|

C10-004 |

41 |

Adult aHUS |

||

|

Supportive care studies |

||||

|

Coppo 2010 |

51 |

Observational registry based studies; follow up ranged from 1 to 7.5 years |

Adult TTP & aHUS |

Survival, ESRD, relapse, flare-up |

|

Kremer Hovinga 2010a |

201 |

Adult and paediatric TTP & aHUS |

Death and time to relapse |

|

|

Noris 2010 |

260 |

Adult and paediatric aHUS |

Remission, death, ESRD, relapse, mutations |

|

|

Fremeaux- Bacchi 2013 |

214 |

Adult and paediatric aHUS |

Death, ESRD, relapse, mutations |

|

|

Australiana TMA registry |

39 |

Adult aHUS |

Death, laboratory outcomes, kidney function |

|

aHUS = atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome; TMA = thrombotic microangiopathy; HRQoL = health related quality of life; CKD = chronic kidney disease; ESRD = end stage renal disease; TTP = thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate.

aUpdated data provided

Natural history of aHUS

The PBAC considered aHUS to be a heterogeneous disease with a wide variation in its natural history and in how it responds to treatment.

The natural history of aHUS is influenced by factors such as the patient’s genetic sub-type, environmental triggers and the stage of disease. The PBAC considered that understanding of the role of these factors, and their impact on disease severity, risk of recurrence, prognosis, or the best treatment option for a patient is currently evolving.

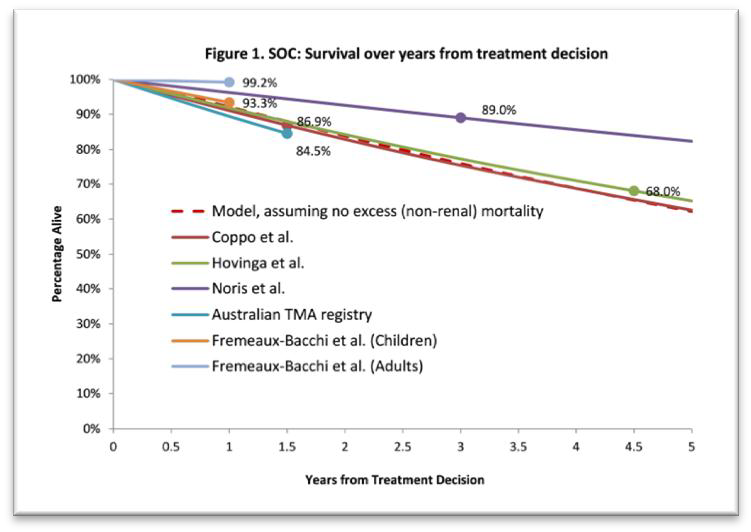

The figure below shows the rates of mortality observed in the supportive care studies.

Standard of Care: Survival over years from treatment decision

Note: Survival is reported at a limited number of time points in each study, and therefore the data is interpolated linearly. Rates of mortality in patients with aHUS are not linear and therefore the figure is indicative only.

The PBAC noted the following issues with the supportive care studies:

- There was no adjustment for the factors that the Committee considered are likely to influence the natural history of aHUS;

- There were no uniform diagnostic criteria for aHUS;

- There was significant heterogeneity in patient characteristics.

The PBAC considered that these differences may contribute to the variation in the mortality rates observed across the studies.

8. Results of Trials

Mortality

The PBAC noted that only two deaths were reported across the four eculizumab studies over three years.

The PBAC noted the comparison of the mortality estimates from the eculizumab studies (pooled data including adults and children) to the mortality estimates from the groups of adult patients included in two of the supportive care studies (Noris 2010 and Fremeaux-Bacchi 2013). The results are provided in the table below. The PBAC noted that there were no statistically significant differences at one and three years.

The PBAC also noted the comparison of the mortality estimates from the eculizumab studies to the mortality estimates from the groups of paediatric patients included in the same two supportive care studies. The PBAC noted that mortality was significantly higher in Noris 2010 compared to the pooled data for eculizumab, with a risk difference at 3 years of -0.13 (95% CI: -0.19, -0.06).

The PBAC noted the limitations of this analysis included that the pooled data from the four eculizumab studies also includes adults, and the patient characteristics are heterogeneous.

|

|

1 year |

2 year |

3 years |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Eculizumab studies a |

|||

|

N (%) |

0/100 (0.0%) |

1/100 (1.0%) |

2/100 (2.0%) c |

|

Supportive care studies |

|||

|

Paediatrics and adult population |

|||

|

Kremer Hovinga 2010 |

|||

|

N (%) |

16/201 (8.0%) d |

32/201 (15.9%) d |

48/201 (23.9%) d |

|

RR (95% CI) b |

0 |

0.06 (0.01, 0.45) |

0.08 (0.02, 0.34) |

|

RD (95% CI) b |

-0.08 (-0.12, -0.04) |

-0.15 (-0.20, -0.10) |

-0.22 (-0.28, -0.15) |

|

Adult population only |

|||

|

Coppo 2010 |

|||

|

N(%) |

4/54 (7.4%) e |

9/54 (16.7%) e |

14/54 (25.9%) e |

|

RR (95% CI) b |

0 |

0.06 (0.01, 0.46) |

0.08 (0.02, 0.33) |

|

RD (95% CI) b |

-0.07 (-0.14, 0.00) |

-0.16 (-0.26, -0.06) |

-0.24 (-0.19, -0.02) |

|

Noris 2010 |

|||

|

N(%) |

2/99 (2.1%) |

NR |

4/99 (4.2%) |

|

RR (95% CI) b |

0 |

|

0.50 (0.09, 2.64) |

|

RD (95% CI) b |

-0.02 (-0.05, 0.01) |

|

-0.02 (-0.07, 0.03) |

|

Fremeau-Bacchi 2013 |

|||

|

N(%) |

1/125 (0.8%) |

NR |

NR |

|

RR (95% CI) b |

0 |

||

|

RD (95% CI) b |

-0.01 (-0.02, 0.01) |

||

|

Paediatrics population only |

|||

|

Noris 2010 |

|||

|

N(%) |

17/149 (11.5%) |

NR |

22/149 (14.6%) |

|

RR (95% CI) b |

0 |

|

0.14 (0.03, 0.56) |

|

RD (95% CI) b |

-0.11 (-0.17,-0.06) |

|

-0.13 (-0.19, -0.06) |

|

Fremeaux-Bacchi 2013 |

|||

|

N(%) |

6/89 (6.7%) |

NR |

NR |

|

RR (95% CI) b |

0 |

||

|

RD (95% CI) b |

-0.07 (-0.12, -0.02) |

||

RR = relative risk; RD = risk difference; CI = confidence interval; italics = calculated during evaluation; bold = statistically significant; NR = not reported.

a Pooled studies

b The relative risk and risk difference are compared to the pooled estimate from the four eculizumab studies

c The median follow-up was 29 months

d Calculated by the re-submission, using incorrect linear assumption of mortality from 32% at a median follow-up of 4.4 years to estimate 1, 2 and 3 year mortality rates

e Calculated by the re-submission, using linear assumptions, the mortality in the publication was reported as 13% with a mean follow up of 17.8 (SD: 24.2) months.

Surrogate outcomes

The PBAC noted that all the eculizumab studies showed that patients treated with eculizumab experienced a significant improvement in TMA response, haematological normalisation, kidney function and quality of life compared to baseline. The results of the eculizumab studies are shown in the table below.

|

Primary Efficacy Outcomes |

26 weeks |

2nd point estimate a |

2 years |

3 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Study C08-002, n=17 |

||||

|

Complete TMA response, n (%; 95% CI) |

11 (65; 38-68) |

13 (76; 50-93) |

13 (76; 50-93) |

13 (76; 50-93) |

|

Haematologic normalisation, n (%; 95% CI) |

13 (76; 50-93) |

15 (88; 64-99) |

15 (88; 64-99) |

15 (88;64-99) |

|

CKD improvement ≥1 stage, n (%; 95% CI) |

10 (59; 33-82) |

11 (65; 38-86) |

12 (71; 44-90) |

13 (76; 50-93) |

|

HRQoL change from baseline (95% CI) |

0.31 (0.2-0.4) |

0.33 (0.2-0.4) |

0.31 (0.3-0.3) |

0.29(0.3-0.3) |

|

Study C08-003, n=20 |

||||

|

Complete TMA response, n (%; 95% CI) |

5 (25; 9-49) |

7 (35; 15-59) |

11 (55; 32-77) |

- |

|

Haematologic normalisation, n (%; 95% CI) |

18 (90; 68-99) |

18 (90; 68-99) |

18 (90; 68-99) |

18 (90 ;68-99) |

|

CKD improvement ≥1 stage, n (%; 95% CI) |

7 (35; 15-59) |

9 (45; 23-68) |

12 (60; 36-81) |

12 (60; 36-81) |

|

HRQoL change from baseline (95% CI) |

0.12 (0.0 -0.2) |

0.13 (0.1-0.2) |

0.14 (0.1-0.2) |

0.16 (-) |

|

Study C10-004, n=41 |

||||

|

Complete TMA response, n (%; 95% CI) |

30 (73;57-86) |

33 (81;65-91) |

- |

- |

|

Haematologic normalisation, n (%; 95% CI) |

36 (88;74-96) |

40 (98;87-100) |

|

|

|

CKD improvement ≥1 stage, n (%; 95% CI) |

17 (45; 29-62) |

- |

- |

- |

|

HRQoL change from baseline (95% CI) |

0.17 (0.1-0.2) |

- |

- |

|

|

All adults and adolescents (C08-002, C8-003 and C10-004), n= 78 |

||||

|

Complete TMA response, n (%) |

46 (59%) |

53 (68%) |

- |

- |

|

Haematologic normalisation, n (%) |

67 (86%) |

73 (94%) |

- |

- |

|

CKD improvement ≥1 stage, n (%) |

34 (44%) |

- |

- |

- |

|

HRQoL change from baseline (weighted) |

0.19 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Study C10-003 (paediatrics), n=22 |

||||

|

Complete TMA response, n (%; 95% CI) |

14 (64;41-83) |

15 (68;45-86) |

- |

- |

|

Haematologic normalisation, n (%; 95% CI) |

18 (82;60-95) |

20 (91;71-99) |

- |

- |

|

CKD improvement ≥1 stage, n (%; 95% CI) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

HRQoL change from baseline (95% CI) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Adults vs paediatrics complete TMA response compared |

||||

|

RR (95% CI) |

0.93 (0.6-1.3) |

1.00 (0.7-1.4) |

- |

- |

|

RD (95% CI) |

-0.05 (-0.3-0.2) |

0 (-0.2-0.2) |

- |

- |

TMA = thrombotic microangiopathy; HRQoL= health related quality of life; CKD = chronic kidney disease

a 64 weeks for C8-002; 62 weeks for C8-003; 10.2 months for C10-003, and 11.5 months for C10-004

The PBAC noted a comparison of the complete TMA response reported in the eculizumab studies with remission rates reported in one of the supportive care studies (Noris 2010) (see table below).

|

|

Eculizumab |

Supportive care |

RR (95% CI) |

RD (95% CI) |

NNT |

|

Complete TMA response with eculizumab compared to complete remission with supportive carea |

|||||

|

Adults |

53 (68%) |

13 (13%) |

5.2 (3.1-8.8) |

0.55 (0.4-0.7) |

2 |

|

Paediatrics |

15 (68%) |

49 (33%) |

2.1 (1.44-3.0) |

0.35 (0.1-0.6) |

3 |

|

Complete TMA response with eculizumab compared to all remission with supportive careb |

|||||

|

Adults |

53 (68%) |

50 (50%) |

1.3 (1.1-1.7) |

0.18 (0.0-0.3) |

6 |

|

Paediatrics |

15 (68%) |

98 (66%) |

1.0 (0.8-1.4) |

0.02 (-0.2-0.2) |

32 |

Source: constructed during evaluation

TMA= thrombotic microangiopathy; RR = relative risk; RD = risk difference; NNT = number needed to treat; CI = confidence interval

aComplete TMA response defined as normalisation of haematological parameters and ≥25% decrease in serum creatinine from baseline as reported in eculizumab studies. Complete remission defined as normalisation of haematologic parameters and renal function as reported in Noris 2010.

bAll remission is complete remission plus partial remission defined as normalisation of haematologic parameters with renal sequelae (chronic renal failure and/or proteinuria _0.2 g/24 h) as reported in Noris 2010.

The PBAC noted that 68% of adult patients treated with eculizumab achieved complete TMA response while only 13% and 50% of adult patients who received supportive care achieved complete remission or remission (complete or partial), respectively.

In the paediatric population, the PBAC noted that 68% of patients treated with eculizumab achieved complete TMA response while 33% and 66% of patients who received supportive care achieved complete remission or remission (complete or partial), respectively

Comparative effectiveness in patients with an acute attack of aHUS

The PBAC considered that there are two groups of patients with aHUS, which broadly align with the two clinical management algorithms presented in the submission:

1. Patients with active, progressive TMA with acute episodes of aHUS, who have not progressed to end stage renal disease;

2. Patients with end stage renal disease on chronic dialysis who are demonstrating extra-renal TMA or who are suitable for a kidney transplant.

The PBAC considered these to be two separate patient groups, and considered the effectiveness of eculizumab compared to supportive care in each of the groups.

The PBAC considered that three of the four eculizumab studies (C10-003 and C10-004 and C08-002) were representative of the first group of patients because these studies excluded patients who received chronic dialysis (defined as dialysis for longer than four months) and the mean time from aHUS diagnosis to study participation was 41 months in C08-002 and 27 months in C10-004. The PBAC considered that the patients included in these three studies were more likely to have recoverable kidney function than the patients included in study C08-003.

The PBAC considered that study C08-003 (n=20) provided information about patients with significant chronic renal impairment, but not necessarily about patients on chronic dialysis with either extra-renal TMA or who were candidates for transplantation. This study recruited patients with a persistent aHUS, chronic renal impairment with stable platelet counts on PE/PI. The mean time from aHUS diagnosis to study enrolment was 87 months. Patients in this study had significant and long standing renal impairment; 50% of patients had severe stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease and 90% had stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease.

As in the table above, the PBAC noted that the incremental improvement in TMA, kidney function and quality of life compared to baseline was higher in the studies that were representative of patients with an acute attack of aHUS than in the studies representative of patients with chronic renal disease.

End stage renal disease avoided

Studies C08-002, C10-003 and C10-004 included 40 patients who were on dialysis that had recently been commenced (within 4 months of trial entry). The PBAC noted that 33 of these 40 patients (82.5%) were able to cease the use of short-term dialysis during eculizumab treatment. These patients remained dialysis-free through two years of treatment.

The PBAC noted that in the supportive care studies, the proportion of patients with aHUS who avoided end stage renal disease at one year was:

- 68% in Noris (32.1% of 260 patients had end stage renal disease after one year of follow-up); and

- 66.4% in Fremeaux-Bacchi 2013 (46% of adults and 16% of children included had ESRD after one year of follow-up).

The PBAC concluded that patients on eculizumab with recently commenced dialysis had a higher rate of end stage renal disease avoided than patients in the supportive care studies (from 68% in one of the supportive care studies to 82.5% across the relevant eculizumab studies).

Clinical questions

The PBAC noted numerous issues that were not adequately addressed in the clinical data presented in the submission:

- It was not possible to quantify how effective eculizumab is in patients with active TMA following a renal transplant. While the studies of eculizumab included some patients who had received a prior kidney transplant and the submission presented a case series of renal transplant recipients treated with eculizumab (Zuber et al, 2012), the PBAC considered that the currently available data were insufficient to determine incremental comparative effectiveness.

- In patients with recurrent aHUS post renal transplant, it was not possible to determine what proportion of patients achieved a complete TMA response nor whether extra-renal acute tissue-damage improved.

- It was not possible to determine how effective eculizumab is in enabling long term success of renal transplantation in patients with end stage kidney failure.

- The clinical benefits for patients who have a renal transplant while on eculizumab were not quantified.

- The rate of development of end stage renal disease over time in patients on eculizumab was not defined in long term follow up.

Based on the eculizumab studies of 3.5 years duration, the PBAC considered that the following key pieces of information could not be determined:

- whether all patients would need routine life-long therapy;

- the consequences of ceasing eculizumab treatment in a patient who has had complete resolution of TMA;

- whether a surrogate marker exists for durable remission;

- the optimal duration of therapy;

- the dose that is required in patients without active TMA to avoid recurrence;

- whether treatment should differ by genetic sub-types or clinical scenarios.

The PBAC noted that there was no claim in the submission that eculizumab reverses end stage renal failure.

With regard to comparative harms, the PBAC noted the common adverse events reported in the eculizumab studies were infections, gastrointestinal disorders and respiratory disorders. Adverse events categorised as severe were anaemia, convulsions, headache, hypertension and chronic renal failure.

The PBAC noted that the comparative safety of long-term eculizumab use is still to be determined. The safety data from the four studies of eculizumab in aHUS was for a maximum follow-up of 3.5 years (with a mean follow-up of 29.4 months across all studies). The PBAC noted that eculizumab therapy may be continued lifelong in some patients, a view that was confirmed by the clinical specialist at the hearing. Further, the PBAC noted that the safety of long-term use of eculizumab in patients with complete remission of TMA and renal function is also not known.

In its March 2013 consideration of eculizumab, the PBAC was concerned that patients treated with eculizumab were more susceptible to meningococcal infection. The post-marketing reporting frequency of meningococcal infection has remained constant over the time, with the rate of infection estimated to be 0.44 per 100 patients-years.

The PBAC noted that the re-submission provided safety information from the supportive care studies for plasma therapy, renal dialysis and transplant. While noting the differences in patient characteristics between the observational and eculizumab studies, the PBAC also noted the significant morbidity and mortality associated with long-term dialysis and renal transplant.

9. Clinical Claim

The re-submission described eculizumab as more effective and safer than current supportive care in treating patients with confirmed aHUS with:

- active and progressing TMA who have not progressed to end stage renal disease; or

- end stage renal failure on chronic dialysis who are either demonstrating extra-renal TMA or who are otherwise suitable for a kidney transplant.

The PBAC considered that eculizumab treatment was associated with reduced mortality and a greater TMA response than supportive care. The PBAC considered that the claim of superior efficacy was supported. However, the PBAC noted the limitations in the comparative data and concluded that the magnitude of the incremental benefit compared to supportive care was difficult to determine with certainty based on the data that are currently available. Therefore the PBAC concluded that, while eculizumab was an effective drug in the treatment of acute episodes of aHUS, the extent of the clinical benefit was difficult to quantify. The PBAC was unable to determine the effectiveness of eculizumab in patients on long term dialysis.

The PBAC noted the significant morbidity and mortality associated with long-term dialysis for patients who do progress to end stage renal failure. However, the PBAC considered that it was important that further information is obtained regarding the risk-benefit profile of long-term eculizumab, and how this differs between patient groups.

10. Economic Analysis

The re-submission presented a modelled economic evaluation (cost-utility analysis), based on the clinical claim of superior efficacy and safety compared to current supportive care.

The PBAC accepted the advice of the ESC that the structure of the model was not appropriate because it only included patients with chronic kidney disease; that is, patients with acute renal failure were not included in the economic model. The PBAC considered that the magnitude of the incremental effectiveness of eculizumab over supportive care was higher in patients with acute renal failure than in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Additionally, the economic model presented in the submission used only renal outcomes to predict mortality in patients on eculizumab. The PBAC agreed with the ESC that other clinically important outcomes such as TMA response should also have been included in order to capture all the potential benefits of eculizumab treatment.

In light of the factors outlined above, the PBAC considered that the structure of the economic model was not representative of real clinical practice in Australia, and that the approach taken by the sponsor made assessment of the cost-effectiveness of eculizumab difficult. Therefore the resulting ICER, which was high, was not considered to be a reliable estimate of the cost-effectiveness of eculizumab in the population proposed by the submission.

Further, the PBAC agreed with the ESC that the duration of the model and many inputs into the model were not reasonable, including that:

- the duration of the model was 97 years (up to a maximum patient age of 125 years), while clinical data were available only for a maximum of 3.5 years.

- the model overestimated the kidney transplant rates for supportive care: it assumed that patients on supportive care have an average of 3.1 kidney transplants with a median survival of 6.5 years, while eculizumab patients receive zero transplants with a median survival of 51 years.

- the model assumed that patients on supportive care have poorer kidney function at the start of the model than those patients on eculizumab.

- the model assumed that patients continue eculizumab treatment even if they progress while receiving treatment. While no stopping rule is proposed by the restriction, this may overestimate the costs for eculizumab.

- the model does not include a post-renal transplant health state.

- the cost offsets were not adequately quantified.

The PBAC concluded that these issues cannot be resolved within the current model structure.

The PBAC concluded that eculizumab would not be able to be demonstrated to be cost-effective under the constraints of the model structure proposed in the submission. The PBAC specifically noted that a key driver of the model was the unit price of eculizumab.

However, in light of the high unmet clinical need, the PBAC considered that eculizumab would likely be cost-effective if the PBS subsidy was limited to patients experiencing their first episode of aHUS who achieve a complete TMA response and normal renal function, or to non-dialysis-dependent patients with recurrent disease who achieve a complete TMA response and whose renal function reverts to their baseline.

The PBAC noted that the cost effectiveness of eculizumab would be significantly affected by the anticipated clinical practice of indefinite continuation of therapy. The PBAC considered that for patients who are able to demonstrate a response to the point that they achieve remission, it would be reasonable for PBS-subsidised treatment to discontinue after six months given that eculizumab is not without side effects, with clinical progress monitored and the need for further treatment assessed.

11. Estimated PBS Usage and Financial Implications

The re-submission estimated a total cost to the PBS of between $100 million and $150 million over the first five years of listing (based on updated Australian population estimates). The previous submission estimated the cost to be higher, while within the same range.

The net cost per year for the PBS remains highly uncertain given the lack of reliable data on the prevalence and incidence of aHUS in Australia, given the rarity of the condition and inconsistent use of diagnostic criteria in the past.

The likely number of patients treated per year was estimated to be less than 100 patients in Year 5, at an estimated net cost per year to the PBS of between $30 – 60 million in Year 5.

The PBAC noted that the estimates are highly sensitive to any small change in patient numbers due to the high acquisition cost of eculizumab.

The PBAC considered that eculizumab would be cost-effective at a price justified by the existing evidence and if the measures discussed below were implemented to contain risks associated with the cost of the drug to the PBS:

- the sponsor should rebate the Commonwealth the price of eculizumab provided to patients who do not achieve a complete remission to treatment;

- under a managed entry scheme, the sponsor agrees to:

(i) price rebates commensurate with the magnitude of the clinical response achieved;

(ii) fund a structured program to collect evidence aimed at resolving the identified areas of uncertainty, including treatment breaks for those patients who have achieved complete remission;

(iii) develop with the PBAC cessation of treatment criteria for patients not achieving a complete response, including definition of an adequate duration of a trial of treatment;

- 100% rebate over the financial estimates in the submission.

- the arrangements for the pricing of eculizumab and the structured program should be provided to the PBAC for review.

Managed Entry Scheme

The PBAC considered that a Managed Entry Scheme for eculizumab in aHUS would address the uncertainties around both the incremental effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of eculizumab compared to supportive care.

A Managed Entry Scheme would enable the listing of eculizumab at a price justified by the existing evidence, as follows:

- the price requested in the submission for those patients with first presentation of aHUS who achieve complete remission and non-dialysis dependent patients with recurrent aHUS who achieve complete remission. The PBAC considered that complete remission would require a patient to have no TMA and to have normal renal function at six months from the initiation of therapy. In patients with recurrent aHUS, complete remission would require no TMA and renal function equivalent to their baseline at six months.

Scaled rebates would be applied for those patients who do not achieve complete remission at 6 months. The sponsor would be required to rebate the Commonwealth:

- a specified percentage of the price of eculizumab for patients initially requiring dialysis who achieve dialysis independence after 6 months of eculizumab therapy.

- a specified percentage of the price of eculizumab for patients who did not require dialysis and who achieve a >25% improvement in renal function where the renal function remains abnormal but is not classified as end stage renal disease.

- the full price of eculizumab in those patients who:

(i) fail to achieve a >25% improvement in renal function;

(ii) die within 6 months; or

(iii) have established end stage renal disease.

The PBAC considered that the key clinical sources of uncertainty which would have prevented this recommendation in the absence of a managed entry scheme and a financial risk share were:

- In patients with an acute presentation of aHUS that resolves:

- whether routine, long-term therapy is required.

In patients with established end stage renal disease:

- whether eculizumab treatment provides a meaningful extension of life.

- whether eculizumab treatment allows kidney transplantation that is successful in the long-term.

In both groups of patients:

- what is the magnitude of the incremental benefit.

- what is the most cost-effective way to use eculizumab in the long term.

- what is the risk:benefit profile of long-term eculizumab therapy in different patient groups.

The PBAC acknowledged that randomised controlled trial evidence for long term treatments of aHUS is unlikely to be forthcoming and considered that other evidence generated under the Managed Entry Scheme would be appropriate in this circumstance. The PBAC considered that the ‘fit-for-purpose’ evidence that the sponsor would need to provide could be obtained as part of a structured program that collects the following data:

- patient outcomes, including rates of dialysis required in short and long term, rates of avoidance of end stage renal disease, rates and degrees of improvements in renal function, TMA response, complete remission, death.

- factors that may modify patient response to eculizumab, particularly a patient’s genetic sub-type and stage of disease.

- the standard initial management of aHUS.

- the safety of eculizumab.

- the duration of treatment required to achieve maximal response, the durability of response with eculizumab, including assessment as to consequences of discontinuation of eculizumab therapy in complete responders.

- the capacity for salvage with eculizumab if eculizumab is ceased after 4 to 6 months in those patients who achieve remission.

- costs of treatment and estimation of cost-offsets.

This program would need to link to registry data, and would require significant involvement of independent clinical leaders and clinical experts in specialised treatment centres.

The PBAC considered that data from the structured program should be placed into the public domain for use by researchers, government and industry alike.

The PBAC requested that the details of this Managed Entry Scheme, including the arrangements for pricing and the structure of the program, be provided for its review prior to incorporation into a deed of agreement between the sponsor and the Commonwealth.

The PBAC requested that the data collected through the managed entry scheme be presented back for its analysis after 12 and 24 months of data are available.

12. PBAC Outcome

The PBAC recommended the listing of eculizumab on the basis that it should be available only through special arrangements under section 100. The PBAC recommended the special arrangements described below.

The PBAC is satisfied that eculizumab provides, for some patients, a significant improvement in efficacy over supportive care - that is for patients with active, progressive TMA during acute episodes of aHUS and who have not progressed to end stage renal disease (ESRD) i.e. greater than four months on dialysis; or for prevalent patients on chronic dialysis demonstrating extra-renal TMA.

As stated in March 2013, at the time the first application for eculizumab in aHUS was considered, the PBAC acknowledged the difficulties associated with obtaining clinical data for the use of eculizumab in the treatment of patients with aHUS disease given the rarity of the condition.

The PBAC noted that the submission requested listing in two distinct groups of patients with aHUS:

- Patients with active, progressive TMA during acute episodes of aHUS, who have not progressed to end stage renal disease;

- Patients with end stage renal disease on chronic dialysis who are demonstrating extra-renal TMA or who are suitable for a kidney transplant.

The PBAC considered that aHUS is a heterogeneous disease and its natural history (including disease severity, prognosis, and course of disease) is influenced by factors such as the genetic subtype, environmental triggers and the stage of the disease. The impact of these factors on the natural history of aHUS is incompletely understood.

The PBAC noted the limitations of the data currently available, including that:

- it was difficult to determine the natural history of aHUS;

- patients included in the supportive care studies may not be sufficiently similar to the patients included in the eculizumab studies to enable a robust comparison;

- outcomes were not uniformly reported across trials; and

- data were not available to determine whether there would be groups who would respond better to treatment than others.

The PBAC noted that all the eculizumab studies showed that patients treated with eculizumab experienced a significant improvement in TMA response, haematological normalisation, kidney function and quality of life compared to baseline.

The PBAC noted that the incremental improvements with eculizumab in TMA, kidney function and quality of life were greater in the studies that were representative of patients who have not progressed to end stage renal disease than in the studies representative of patients with later-stage aHUS. Further, in patients with recently commenced dialysis, eculizumab may prevent progression to end stage renal disease and the PBAC considered this to be a very clinically important benefit.

The PBAC concluded that there is a high clinical need for eculizumab in aHUS, particularly in those patients with an acute episode who have not progressed to end stage renal disease. The PBAC formed this view because it noted:

- aHUS is a severe disease associated with end stage renal disease and mortality, particularly at its first presentation.

- The submission estimated the prevalence of aHUS to be 3.3 to 7 cases per million.

- Patients are currently treated with supportive care consisting of plasma exchange/infusion, dialysis and/or renal transplant. There is high morbidity and mortality associated with dialysis and renal transplant.

- The PBAC considered that the clinical data indicated that eculizumab was more effective than supportive care with respect to the outcomes of mortality and TMA response. Further the PBAC noted that, in those patients who have only recently commenced dialysis, eculizumab may prevent progression to end stage renal disease.

The PBAC considered that the structure and inputs of the economic model do not capture the full benefits of eculizumab treatment in this disease, and concluded that eculizumab would be likely to be cost effective in patients who achieve a complete response to treatment.

The PBAC also acknowledged the strong consumer support for subsidised access to eculizumab in aHUS.

The PBAC recommended that access to the listing be by written Authority application, to be handled by the Complex Drugs area of the Department of Human Services.

In accordance with subsection 101(3BA) of the National Health Act 1953, the PBAC advised that it is of the opinion that, on the basis of the material available to it at its March 2014 meeting, eculizumab should not be treated as interchangeable on an individual patient basis with any other drug(s) or medicinal preparation(s).

The PBAC advised that eculizumab is not suitable for inclusion in the list of medicines for prescribing by nurse practitioners.

The PBAC noted that this outcome does not meet the criteria for an independent review.

Recommendation:

Add new item:

Restriction to be finalised

13. Context for Decision

The PBAC helps decide whether and, if so, how medicines should be subsidised in Australia. It considers submissions in this context. A PBAC decision not to recommend listing or not to recommend changing a listing does not represent a final PBAC view about the merits of the medicine. A company can resubmit to the PBAC or seek independent review of the PBAC decision.

14. Sponsor’s Comment

Alexion welcomes the March PBAC positive recommendation to list eculizumab for patients with aHUS via the PBS, recognising that eculizumab is a clinically effective treatment for aHUS, meeting a substantial unmet clinical need and providing significant benefit over supportive care, including improved survival. However, there are a number of serious clinical, ethical and administrative concerns with the criteria and conditions for funded access for aHUS patients in Australia from these recommendations Alexion has been proposing solutions to Government for since May.

aHUS is a chronic and progressive disease that causes systemic TMA-mediated organ damage. Progressive organ damage is constant, and organ failure or a severe complication can occur at any time during the disease course, leaving patients who survive an overt clinical TMA manifestation at constant risk of progressive TMA damage and sudden death. The TGA-approved product information states that “SOLIRIS treatment is recommended to continue for the patient’s lifetime,” unless the discontinuation of eculizumabis clinically indicated, which addresses the chronic and progressive nature of the disease.

It is Alexion’s intent to continue to work closely with the Department of Health and all of Government to finalise these prescribing and managed entry criteria, and find rapid solutions for access to funded eculizumab therapy for aHUS patients at highest risk from this ultra-rare, progressive and life threatening disease. We look forward to creating a unique and sustainable funding model for eculizumab in aHUS, for all stakeholders; from Government to patients.