Pazopanib, tablets, 200 mg and 400 mg (as hydrochloride), Votrient®

Public Summary Document

Product: Pazopanib, tablets, 200 mg and 400 mg (as hydrochloride), Votrient®

Sponsor: Glaxo Smith Kline Australia Pty Ltd

Date of PBAC Consideration: November 2012

1. Purpose of Application

To extend the recommended Authority Required listing to include the initial and continuing treatment of advanced (unresectable and/or metastatic) soft tissue sarcoma in a patient who meets certain criteria.

2. Background

This was the first submission for pazopanib for an extension to the recommended Authority Required listing to include the initial and continuing treatment of advanced (unresectable and/or metastatic) soft tissue sarcoma in a patient who meets certain criteria.

PBAC considered pazopanib for renal cell carcinoma in March 2012 and July 2010.

At its July 2010 meeting, the PBAC rejected an application for listing of pazopanib because the proposed PBS-restriction was clinically inappropriate and did not reflect the treatment algorithm which would result if pazopanib were to be PBS-listed. Additionally, based on the data available at the time, there was significant uncertainty as to whether pazopanib is non-inferior to sunitinib in the treatment of stage IV advanced and/or metastatic, clear cell variant, renal cell carcinoma.

At its March 2012 meeting, the PBAC recommended listing pazopanib on the PBS as the sole PBS-subsidised therapy for certain patients with renal cell carcinoma on a cost-minimisation basis compared with sunitinib, whilst also noting that some considerations previously relevant to sunitinib do not apply to pazopanib. The PBAC advised that the relevant dose relativity in this context is 1 mg sunitinib to 24 mg pazopanib.

3. Registration Status

At the time of PBAC consideration in November 2012, pazopanib was TGA registered for use in the treatment of advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Pazopanib was approved by the TGA as an orphan drug for the treatment of patients with advanced (unresectable and/or metastatic) soft tissue sarcoma on 13 May 2011.

Pazopanib was approved by the TGA for the following additional indication on 20 November 2012:

- Treatment of patients with advanced (unresectable and/or metastatic) Soft Tissue Sarcoma (STS) in patients who, unless otherwise contraindicated, have received prior chemotherapy including an anthracycline treatment. The Phase III trial population excluded patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) or adipocytic soft tissue sarcoma.

4. Listing Requested and PBAC’s View

Authority required

Initial treatment, as sole PBS-subsidised therapy, of advanced (unresectable and/or metastatic) soft tissue sarcoma, in a patient who has a WHO performance status of 2 or less, and has received prior anthracycline treatment or in whom anthracycline treatment is inappropriate. Patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) and adipocytic soft tissue sarcoma are not included in the criteria.

NOTE:

No applications for increased quantities and/or repeats will be authorised.

Authority required

Continuing treatment beyond 3 months, as sole PBS-subsidised therapy, of advanced (unresectable and/or metastatic) soft tissue sarcoma in a patient who has previously been issued with an authority prescription for pazopanib and who has stable or responding disease according to RECIST criteria.

NOTE:

RECIST Criteria is defined as follows:

- Complete response (CR) is disappearance of all target lesions;

- Partial response (PR) is a 30% decrease in the sum of the longest diameter of target lesions;

- Progressive disease (PD) is a 20% increase in the sum of the longest diameter of target lesions;

- Stable disease (SD) is small changes that do not meet above criteria.

NOTE:

No applications for increased quantities and/or repeats will be authorised.

For PBAC’s view, see Recommendations and Reasons.

5. Clinical Place for the Proposed Therapy

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are a relatively uncommon group of malignancies. Current treatment options for soft tissue sarcoma (STS) are usually palliative and include surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. For patients with advanced (unresectable and/or metastatic) STS who have failed anthracycline treatment as first-line therapy, treatment patterns in second and third line systemic treatment is less clear.

The submission proposed that pazopanib, a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, may be considered as an option following anthracycline therapy or when anthracycline therapy is inappropriate.

The submission noted that the ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology) guidelines (ESMO 2010) recommend that the standard first line treatment is based on doxorubicin regimens, single agent doxorubicin or in combination with ifosfamide. Following failure of doxorubicin, there is no recognised standard second line plus therapy.

The proposed algorithm did not consider pazopanib for first line treatment. The PBAC considered that this was not appropriate since the proposed restriction considers patients in whom anthracycline treatment is inappropriate and therefore may be used in first line therapy. However, the submission claimed that the extent of use in the first line setting would be small.

6. Comparator

The submission nominated best supportive care (BSC) as the main comparator. The submission also nominated a mixed comparator (70% BSC + 30% ifosfamide) for a supplementary analysis.

The PBAC considered that the choice of comparator, although not ideal, was reasonable; however, the PBAC noted that ifosfamide is also an appropriate main comparator in first-line treatment for patients unable to use anthracyclines.

For PBAC’s view, see Recommendation and Reasons.

7. Clinical Trials

The submission presented one randomised trial (VEG110727 or PALETTE) comparing pazopanib 800 mg with BSC in 369 patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma. In the key clinical trial VEG110727, adult patients were recruited on the basis that they had metastatic STS, and had received up to four prior treatments for advanced disease where no more than two lines have been combination regimens. The proposed PBS restriction did not specify that patients must have no more than two lines of combination regimens. The proposed restriction also did not specify that patients must have less than five prior treatments for advanced disease.

In the key clinical trial VEG110727, patients were recruited with a WHO performance status 0-1. This was not consistent with the proposed restriction where patients can have a WHO performance status 0-2.

The published trials presented in the submission are shown below.

|

Trial ID/First author |

Publication title |

Publication citation |

|---|---|---|

|

VEG110727 [PALETTE]

Van Der Graaf et al.

Van Der Graaf et al. |

Prognostic and predictive factors in advanced soft tissue sarcoma patients treated in an EORTC STBSG global network randomized double blind phase III trial of pazopanib versus placebo (EORTC 62072, PALETTE).

Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. |

European Journal of Cancer (2011); 47 (S1): S662

Lancet (2012); 379 (9829): 1879-1886 |

8. Results of Trials

The primary efficacy outcome was progression free survival (PFS), and overall survival was a key secondary outcome. The table below provides the published results of the primary outcome from trial VEG110727.

|

Trial VEG110727 |

Pazopanib N=246 |

BSC N=123 |

|---|---|---|

|

Time to progression, weeks (95% CI) |

|

|

|

50% median |

20.0 (17.9, 21.3) |

7.0 (4.4, 8.1) |

|

Adjusted hazard ratio |

0.35 (0.26, 0.48) p<0.001 |

|

BSC= Best supportive care; CI = confidence interval.

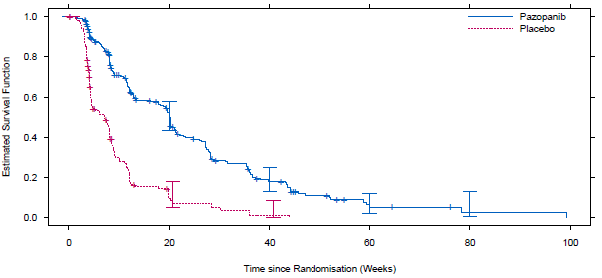

The figure below illustrates the results of PFS curves observed between the two treatment arms.

Kaplan Meier graph of PFS per independent radiologist assessment

|

Subjects at risk |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pazopanib |

246 |

88 |

25 |

5 |

1 |

|

BSC |

123 |

8 |

1 |

|

|

Pazopanib resulted in a statistically significant improvement on PFS compared to BSC (HR 0.35; 95%CI: 0.26 to 0.48; p<0.001; median survival pazopanib = 20 weeks (95% CI: 17.9; 21.3) vs. BSC = 7 weeks (95% CI: 4.4; 8.1)).

For the secondary outcome of overall survival, the results favoured pazopanib over best supportive care but did not reach statistical significance.

The submission stated that the final overall survival analysis was conducted when 280 death events (76% of the patients) had occurred in trial VEG110727 (i.e. 11 months after the primary analysis.

The sponsor disagreed with the evaluation that the claim of superior efficacy is not adequately supported, and argued that pazopanib for the treatment of STS (in comparison to BSC) has been approved by the US FDA, the EMA and the TGA. The sponsor argued that the approval was on the basis of primary evidence from the pivotal Phase III study VEG110727 and supported by the Phase II study, VEG20002, which indicates a favourable benefit risk balance.

The trial VEG110727 allowed patients to be treated with follow-up therapy (including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy) following progression on randomised treatment. There was an imbalance of active treatments after disease progression, with more patients in the placebo arm receiving active therapy. Post-treatment was not presented in the proposed treatment algorithm. The submission also mentioned that overall survival analyses were not adjusted for post-treatment anti-cancer therapy, and suggested that this is likely to bias overall survival results.

The PBAC noted despite the selection of ifosfamide as part of a mixed secondary comparator, no data were presented to compare pazopanib with ifosfamide for comparative efficacy and safety in a first-line setting.

Patients treated with pazopanib were more likely to have adverse events compared to the placebo group. Most adverse events were related to study treatment. The most common grade 3 and 4 adverse events were diarrhoea, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and hypertension.

The submission has provided additional data on potential safety concerns beyond those identified in the clinical trial VEG110727. Study VEG20002 was a Phase II multi-centre, open-label trial that was designed to evaluate the therapeutic activity, safety and tolerability of pazopanib 800 mg once daily. A total of 142 patients were enrolled. Most adverse events in trial VEG20002 refer to fatigue, diarrhoea, hypertension, nausea/vomiting, skin hypopigmentation, and tumour pain.

For PBAC’s view, see Recommendation and Reasons.

9. Clinical Claim

The submission described pazopanib treatment as superior in terms of comparative effectiveness and inferior in terms of comparative safety over best supportive care. Overall, the PBAC considered that the claim for superior efficacy in terms of overall survival is not adequately supported. The claim for inferior safety to BSC was considered to be appropriate.

10. Economic Analysis

The submission presented a cost-utility analysis based on a superiority claim for comparative benefit and inferiority claim for comparative harms. Efficacy inputs are from trial VEG110727. When comparing pazopanib to best supportive care, the submission presented an ICER per life years gained in the range of $45,000-$75,000 and an ICER per QALY in the same range. When comparing pazopanib to the mixed comparator (70% BSC + 30% ifosfamide), the submission presented an ICER per LYG in the range of $45,000-$75,000 and an ICER per QALY in the same range.

The submission did not provide a stepped economic evaluation, including a trial-based economic evaluation. The submission noted that the economic model was structured as a three state Markov-like model with three alternative treatment pathways - pazopanib, best supportive care (placebo), and mixed comparator (70% BSC + 30% ifosfamide).

The three health states were:

- Initial disease: advanced STS of WHO performance status ? 2, where the patient had received prior treatment with an anthracycline or for whom anthracycline treatment was inappropriate.

- Progressive disease: At least a 20% increase in the sum of the longest diameter of target lesions, appearance of one or more new lesions and/or unequivocal progression of existing non-target lesions; This definition of progressive disease was different than the one in the proposed PBS restriction. The PBS restriction only included the criterion of 20% increase in the sum of the longest diameter of target lesions.

- Death: death from any cause.

For PBAC’s view, see Recommendation and Reasons.

11. Estimated PBS Usage and Financial Implications

The likely number of patients per year was estimated in the submission to be less than 10,000 in Year 5, at an estimated net cost per year to the PBS of less than $10 million in Year 5.

The PBAC considered the estimated number of patients to be treated to be a likely underestimate because:

- The proportion of patients likely to go on to develop metastatic disease was uncertain.

- There may be a greater proportion of patients substituting systemic anticancer treatment with pazopanib in both second- and third-line treatment (underestimate).

- The percentage of patients for whom anthracycline therapy is inappropriate as a first line therapy was not well justified.

The submission incorrectly included the inpatient costs of ifosfamide plus MESNA as State and Territory costs.

The PBAC noted that the model did not consider costs for standard follow-up diagnostic tests (e.g. MRI/MRA, PET/CT, US) or visits from an oncologist for palliative care in the cost to government estimates, which may be more frequent in treatment arm vs BSC.

12. Recommendation and Reasons

The major submission proposed an extension to the current Authority Required listing to include the initial and continuing treatment of advanced (unresectable and/or metastatic) soft tissue sarcoma (STS).

The submission nominated best supportive care (BSC) as the main comparator, on the basis that standard treatment options following failure of anthracycline chemotherapy are not defined by clinical guidelines. The submission also nominated a mixed comparator (70% BSC + 30% ifosfamide) in a supplementary analysis. The PBAC considered that the choice of comparator, although not ideal, was reasonable; however the PBAC noted that ifosfamide is also an appropriate main comparator in first-line treatment for patients unable to use anthracyclines.

The proposed restriction and clinical algorithm placed pazopanib as a treatment option for STS for patients following failure of anthracycline therapy (second line treatment) or for whom anthracycline therapy is inappropriate (first line treatment). The PBAC considered that pazopanib would be appropriately placed as a second-line option. The PBAC noted that the proposed restriction would permit use as a first-line option in patients for whom anthracycline therapy is inappropriate, although the sponsor claimed that the extent of use in first line was likely to be small. The PBAC noted that the pivotal trial VEG110727 (PALETTE) recruited patients who were naïve to angiogenesis inhibitors and considered that the PBS restriction should exclude patients who had received prior treatment with angiogenesis inhibitors.

The submission claimed superiority of pazopanib over best supportive care in terms of comparative effectiveness and inferior in terms of comparative safety. Overall, the PBAC considered that the claim for superior efficacy in terms of overall survival is not adequately supported. The claim for inferior safety to BSC was considered to be appropriate.

The PALETTE trial was a Phase III trial comparing pazopanib against BSC in 369 patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma. Patients were randomised to the pazopanib and BSC arms in a ratio of 2:1. The primary outcome was progression free survival (PFS) and the secondary outcome was overall survival (OS). The duration of treatment for the pazopanib arm was 16.4 weeks and 8.1 weeks for the placebo arm (Van Der Graaf et al. 2012). The trial did not have a crossover from placebo to treatment arms. More placebo patients than pazopanib patients who experienced disease progression received post-treatment anticancer therapy (PTACT). Many different PTACT regimens were used, however the submission derived estimates only for the most common ones; gemcitabine with docetaxel, gemcitabine only, dacarbazine (not PBS-listed), and ifosfamide. The estimated number of lines of PTACT was greater for the placebo arm compared to the pazopanib arm.

To inform the supplementary mixed comparator analysis of pazopanib, the submission presented one phase II trial from Van Oosterom (2002), which evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of two regimens of ifosfamide metastatic STS patients given as first- and second-line chemotherapy. The submission did not provide sufficient evidence to assess the quality of the trial, baseline characteristics, and methods of assessment to allow evaluation of the comparability this trial with the PALETTE trial. An unadjusted indirect treatment comparison of the Kaplan Meier curves indicated inferior PFS benefit for ifosfamide compared with pazopanib (HR = 1.1 (0.88-1.38)) and comparable OS benefit (HR = 1.0). As the comparability of the trials could not be determined, the PBAC did not consider that these analyses were sufficiently robust to support the submission’s claim of superiority of pazopanib over ifosfamide for comparative efficacy.

Pazopanib resulted in a statistically significant improvement on PFS compared to BSC (HR 0.35; 95%CI: 0.26 to 0.48; p<0.001; median survival pazopanib = 20 weeks (95% CI: 17.9; 21.3) vs. BSC = 7 weeks (95% CI: 4.4; 8.1)). OS favoured pazopanib over best BSC but did not reach statistical significance. The PBAC noted despite the selection of ifosfamide as part of a mixed secondary comparator, no data were presented to compare pazopanib with ifosfamide for comparative efficacy and safety in a first-line setting.

Patients treated with pazopanib were more likely to have adverse events (AEs) compared to the placebo group. Most adverse events were related to study treatment. The most common grade 3 and 4 adverse events were diarrhoea, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and hypertension. The PBAC noted that the most recent Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSUR) for pazopanib resulted in the amendment of the Warnings and Precautions section to include an update to hypertension, cardiac dysfunction, venous thrombotic events and the potential for infection.

The submission presented a cost-utility analysis using a three state Markov-like model with three alternative treatment pathways. The three treatment pathways were pazopanib 800 mg, best supportive care (placebo), and mixed comparator (70% BSC + 30% ifosfamide). The three health states were initial disease, progressive disease and death. The PBAC noted that the model of three alternative treatment pathways is inconsistent with the proposed clinical algorithm whereby patients progress through anthracycline chemotherapy to pazopanib and then to BSC. In addition, the model was not consistent with the trial population and the proposed PBS restriction. Overall, however, the PBAC considered that the model structure was reasonable.

In the economic model the expected discounted life years gained were greater for pazopanib than for BSC. The PBAC noted that this was longer than the median survival in the clinical trial. The PBAC noted also that the results for OS gain in the PALETTE trial were not statistically significant. The PBAC therefore considered that the modelled OS advantage of pazopanib was unlikely to be observed in clinical practice.

The submission included costs for treatment of adverse events only for anaemia, diarrhoea febrile neutropenia, nausea/vomiting, thrombocytopenia, ALT elevation and AST elevation. The PBAC noted that the Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRG) costs are in general for shorter hospitalisation than the duration of the Grade 3-4 events presented in the submission. For instance, the AR-DRG G70B for diarrhoea has an average duration of hospitalisation of 2.08 days, while the submission claimed an average duration of grade 3 to 4 diarrhoea in the trial was 30 days. As the cost of treating grade 3 to 4 diarrhoea was $2,181 (sourced from the AR-DRG) it was considered by the PBAC this to underestimate the true costs of managing treatment-related adverse events, thereby favouring pazopanib. Additionally, the PBAC noted the exclusion of costs to manage life-threatening AEs such as cardiac dysfunction, venous thrombotic events and the potential for infection detailed in the most recent PSUR. The exclusion of these costs associated with pazopanib was considered inappropriate.

The PBAC noted that the higher PTACT cost assumed for placebo patients was driven by the assumption that patients in the placebo arm begin receiving PTACT sooner and cycle through more lines of therapy compared with patients in the pazopanib arm. The PBAC considered the calculation of PTACT costs was implausible and biased in favour of pazopanib. Because the submission did not attempt to model receipt of PTACT beyond the maximum follow-up of the PALETTE trial, the PBAC considered that the cost of AEs were over-represented in the placebo arm. The PBAC noted that the model did not consider costs for standard follow-up diagnostic tests (e.g. MRI/MRA, PET/CT, US) or visits from an oncologist for palliative care.

The incremental cost per QALY for pazopanib compared to BSC was in the range $45,000-$75,000 and for pazopanib compared to the mixed comparator (70% BSC + 30% ifosfamide) was in the range $45,000-$75,000. The PBAC considered the ICER for the mixed comparator highly uncertain. The PBAC noted that an assumption of equivalent costs for PTACT between pazopanib and placebo arms resulted in an ICER of in the range $75,000-$105,000, a figure that the PBAC considered reflected a more realistic projection of post-treatment costs.

The price of a 136 day course of pazopanib was projected to cost in the range $15,000-$45,000, based on the average trial daily dose as reported in the study. This was less than the dose of 800 mg per day which would be used in clinical practice. The total PBS impact was less than $10 million over 5 years to treat less than 10,000 patients. The PBAC considered that the projected patient numbers were likely to be underestimated because of uncertainty over the proportion of patients likely to develop metastatic disease, a potentially greater proportion of patients substituting systemic anticancer treatment with pazopanib in both second- and third-line treatment and inadequate justification of the percentage of patients for whom anthracycline therapy is inappropriate as a first line therapy. The PBAC also noted the high risk of leakage into other cancers such as Ewing sarcoma, desmoplastic round cell tumours and rhabdomyosarcoma. Therefore the PBAC considered the utilisation and financial estimates to be unreliable.

The PBAC rejected the submission of the basis of an unacceptably high ICER. The PBAC considered that any resubmission would need to remove inappropriately claimed cost offsets, include costs for management of major recently-identified adverse events (e.g. liver failure, MI) and amend the restriction to accurately reflect the trial population.

Recommendation:

Reject

13. Context for Decision

The PBAC helps decide whether and, if so, how medicines should be subsidised in Australia. It considers submissions in this context. A PBAC decision not to recommend listing or not to recommend changing a listing does not represent a final PBAC view about the merits of the medicine. A company can resubmit to the PBAC or seek independent review of the PBAC decision.

14. Sponsor’s Comment

GlaxoSmithKline is disappointed with the PBAC decision, but remains committed to working with the PBAC to make pazopanib available on the PBS for patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma.