Submission to Post-Market Review of PBS Medicines Used to Treat Asthma in Children

Submission 13 - National Asthma Council Australia

Introduction

The National Asthma Council Australia (NAC) produces the national treatment guidelines for asthma which were first published by the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand in 1989 in the Medical Journal of Australia. At that time, the newly formed NAC was asked to produce the guidelines in a format and language suitable for general practice and to ensure thorough national distribution and implementation. The seventh edition of the guidelines is now underway with publication set for November 2013. As has been the practice for many years, some 80,000 copies will be distributed over three years or so to all GPs, pharmacists, practice nurses, asthma educators, allergists, respiratory physicians and pharmacy and medical students. The guidelines have been available on the internet since 1996, and in 2013 will have a dedicated and state of the art website which will include all the references. Some eighty experts from the fields of general practice, allergy, respiratory medicine, pharmacy, asthma education and other relevant areas are involved in the production of the guidelines which involves a number of systematic reviews.

Implementation of the guidelines takes place in many ways and by a number of organisations working in the asthma field. The NAC conducts an extensive educational program, the GP and Allied Health Professionals Asthma and Respiratory Education Program, for primary care in all Medicare Locals with a focus on rural and remote areas, and conducts workshops at most annual major primary care conferences.

The intensive efforts of the NAC in guidelines distribution, promotion and in many educational activities, has created 89% awareness of the Asthma Management Handbook by GPs but fewer than 40% were familiar with guidelines recommendations.1

The guidelines, the Asthma Management Handbook2 (to be renamed the Australian Asthma Handbook for the upcoming edition), have been recognised since their inception as the Australian standard for the treatment of asthma. The treatment of paediatric patients is always an important section of the Handbook, and the NAC is advised by the leading paediatric respiratory physicians and the evidence. The NAC’s much visited website also has a number of resources on paediatric asthma for health professionals and for patients. This review is therefore of particular interest to the NAC. Paediatric respiratory physicians also provide information to primary care health professionals on a regular basis. 3,4

Terms of Reference

The Terms of Reference for the Review are to:

136. Review the evidence on the efficacy and safety of single ingredient and combination product use of inhaled long acting beta2 agonist in children not previously considered by the PBAC in making recommendations to the Minister.

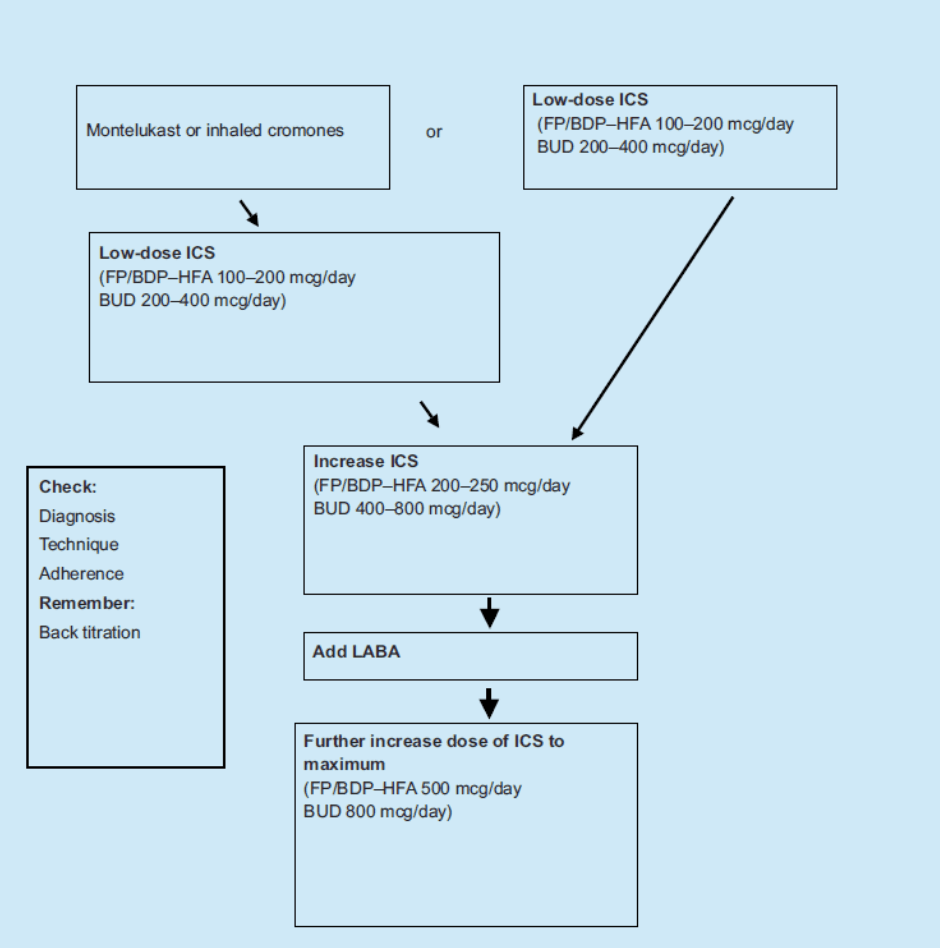

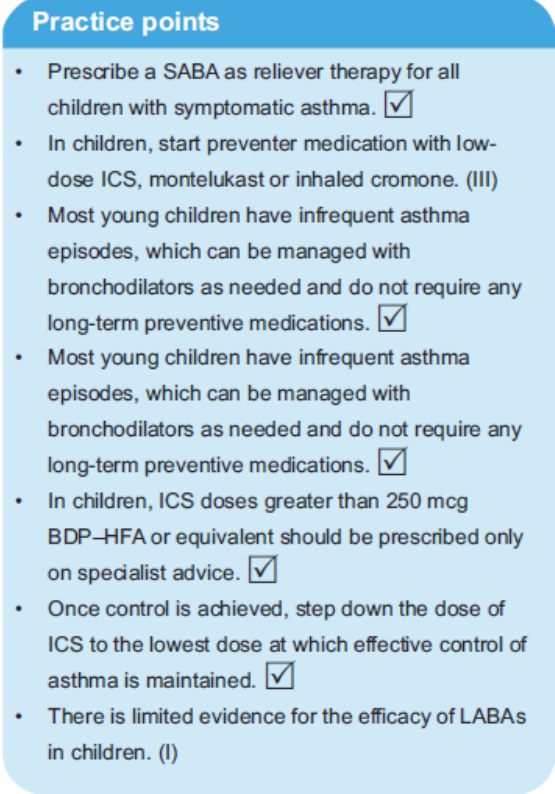

The NAC was unable to discover which evidence the PBAC had considered in making its recommendations to the Minister. However the evidence which must be considered is that which leads to the recommendations in the treatment guidelines for asthma, the Asthma Management Handbook 2006. The following figure from the Handbook (page 24) describes the regimen for preventer therapy in children:

Preventer therapy in children

The points in this table are further summarised under “Principles of drug treatment in children and adolescents” (page 22):

137. Review the DUSC report on utilisation of combination inhaled ICS/LABA considered by PBAC and supplement this analysis with any additional data and clinical information sources available in Australia.

138. Identify areas of prescribing for childhood asthma in Australia where clinical practice is inconsistent with clinical guidelines; and if there is evidence that supports this practice.

The response to these two terms of reference is combined.

The NAC received the DUSC report just as it was finalising its submission so there was not time to examine it in detail but this submission addresses the main points. However, Cost Considerations of Therapeutic Options for Children with Asthma reports on the inappropriate prescribing of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and ICS/long-acting beta agonist (LABA) combination inhalers. 5 The latter should only be used for the 5% of children with asthma who have persistent asthma. This increase in prescribing of ICS and ICS/LABA occurred during the period 1999–2009 when the prevalence of persistent asthma in children dropped from 7.6% to 2.6%.

A number of studies in Australia and the United Kingdom indicate alarming facts such as:

- 2.5% of all children <15 were prescribed an ICS/LABA inhaler, 2009-10 (Medicare Australia unpublished data).

- Of these, 38% had not been prescribed an ICS in the preceding 12 months.

(Medicare Australia unpublished data).

59% of these children had only been prescribed one inhaler in the 12 month period suggesting intermittent use which is not clinically warranted or appropriate.

- 5.7% of all ICS/LABA inhalers dispensed to children <15 were to children < 4 so both inappropriate and potentially dangerous.

- Some children were even dispensed LABA alone which is inappropriate.

Clearly, the national treatment guidelines are not being followed by many primary care practitioners.

According to van Asperen et al.,6 “Although it is common to add a long-acting ?-agonist to inhaled corticosteroids (as a single combination inhaler) there are few paediatric studies examining this practice, and these suggest that, while the combination improves lung function, it does not reduce exacerbation risk — in fact, it may increase it. These recent studies support the current National Asthma Council recommendations of reserving the addition of long-acting ?-agonists for children with asthma that is not adequately controlled by 200–250 ?g/day fluticasone propionate or equivalent doses of other inhaled corticosteroids... The use of long-acting ?-agonists is not, however, recommended for children aged 5 years or younger.”

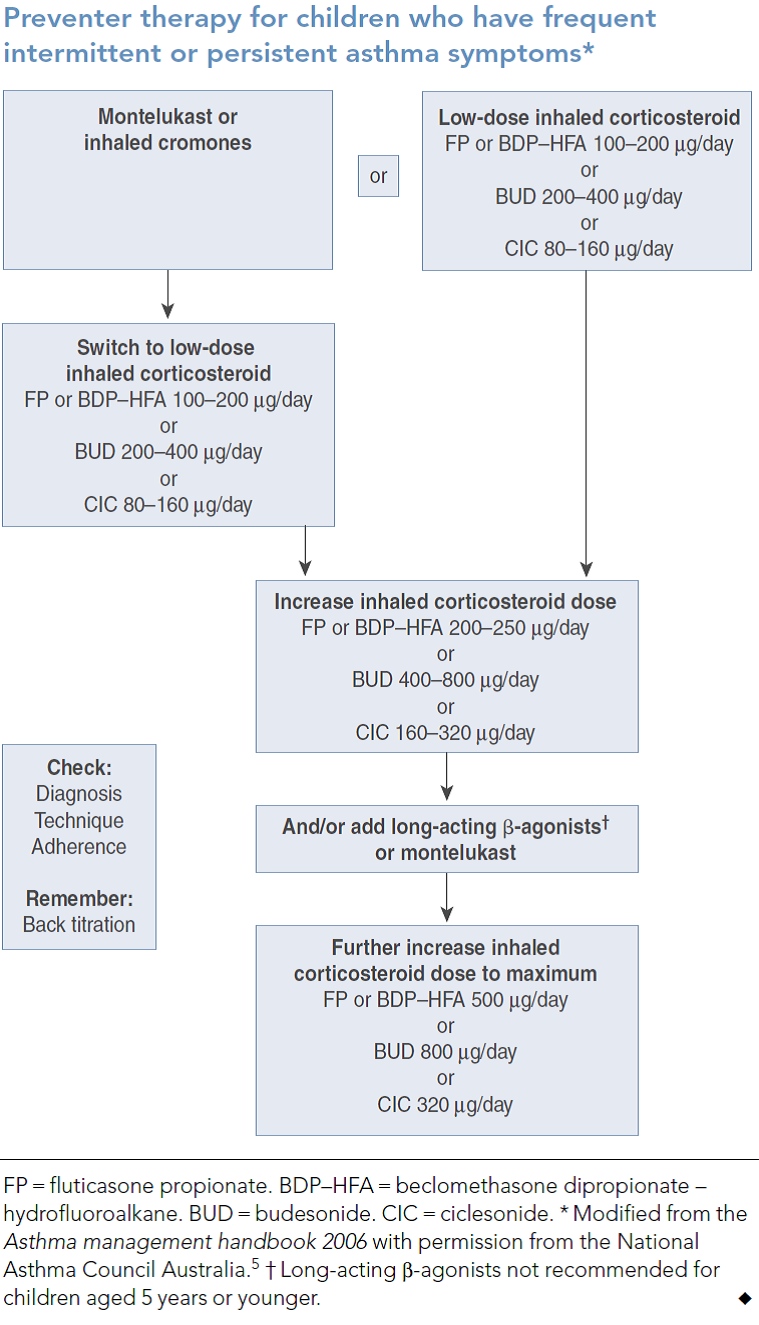

The following table from van Asperen et al.6 updates that already cited from the Asthma Management Handbook as it includes ciclesonide and an extra indication for montelukast as an alternative to LABA. A recent international study by Lemanske Jr et al. 7 reports that children with persistent asthma who were not controlled on low dose single agent ICS may benefit from the addition of a LABA, doubling the dose of ICS or the addition on montelukast. There was clear variability to each individual child’s response to the different treatment strategies.

139. Identify and review recent (past five years) healthcare professional and consumer education in the area of medication management in children with asthma.

There has been no specific or dedicated program for paediatric asthma for health professionals or consumers. The NAC probably has conducted the most extensive national program (funded under the former Asthma Management Program of the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing) for the last twelve years. The topics offered to Medicare Locals (formerly Divisions of General Practice) across Australia include spirometry as well as modules on some 13 asthma topics, including paediatric asthma, and are available to GPs, practice nurses, pharmacists, Aboriginal Health Workers, asthma educators and some other health professionals. Each Medicare Local selects the workshop types or topics which suit the needs of its health professionals. From 2010 to the end of 2012, paediatric asthma was chosen for 27 of the 66 relevant workshop types (Primary Care Asthma Update), the more popular topics were device use, acute asthma, asthma and COPD and Asthma Cycle of Care (NAC unpublished data). The NAC conducts process evaluation of this program with good results but not especially pertinent to paediatric asthma.

140. Identify effective interventions that have resulted in improvement of prescribing and quality use of medicines in the context of childhood asthma using overseas or Australian literature.

The Practitioner Asthma Communication and Education (PACE) program1 emanating from the University of Michigan is an educational intervention to enhance the care of children with asthma by primary care physicians. It provides doctors with evidence-based management guidelines and communication skills for use during consultations to help parents manage their children’s asthma. Trials in the USA showed that doctors’ participation in the PACE program improves patients’ asthma outcomes and carer satisfaction. An expert panel was convened to adapt this program for Australia and an initial feasibility was conducted, followed by a RCT to measure the impact of the PACE program on the processes, costs and outcomes of GP management of children with asthma in Australia. The RCT demonstrated that the PACE workshops for GPs improved a number of critical aspects in the delivery of quality primary care to children with asthma and their families, including more appropriate prescribing of ICS and more appropriate use by the children.8

The NAC and the PACE group plan to include the PACE workshops in the next iteration of the NAC’s GP and Allied Health Professionals Asthma and Respiratory Education Program for which funding has just been announced.

Discussion

Chuang and Jaffe state that “…despite the wide dissemination and recognition of various asthma guidelines, medical practitioners still may not follow guidelines for various reasons.

These include not believing the guidelines are relevant to their practice, lack of familiarity with the guidelines, lack of agreement, lack of outcome expectancy, time pressures, inertia of current practice, lack of supporting staff, and, for the youngest patients, lack of appropriate formulations.”5

Certainly, in Australia, guideline dissemination and implementation through many educational activities and resources has been extensive. The PMAG and DUSC findings on the inappropriate prescribing of fixed dose combination in children are concerning. It is clear that a more specific educational campaign needs to be undertaken in primary care on appropriate prescribing in paediatric asthma.

Recommendations

The current approved lower age limits of prescription for Seretide and Symbicort are 4 and 12 years respectively and neither the TSANZ9 nor Global Initiative for Asthma Guidelines10 recommend the use of LABAS for children 5 years and younger.11

So, to address the current issue of inappropriate prescription of combination medication, all medications containing LABAs should require authority prescription for children under 12, with the indication being; child over 5 years of age with a documented diagnosis of persistent asthma in accordance with the Asthma Management Handbook (to be renamed the Australian Asthma Handbook), and treatment for at least six weeks with an inhaled corticosteroid, who has persistent non-exercise related symptoms requiring reliever medication.

This authority could be a streamlined authority provided there was ongoing monitoring to ensure that LABA add-on prescribing was appropriate and consistent with the treatment guidelines. This recommendation would not restrict GPs or paediatricians prescribing LABA add-on but would put the onus on them to ensure that their prescribing of LABAs was appropriate.

It should be noted that the seventh edition of the Asthma Management Handbook (to be renamed the Australian Asthma Handbook) will be launched in November 2013 and its recommendations for paediatric asthma will be consistent of those in the 2010 TSANZ position paper on The Role of Corticosteroids in the Management of Childhood Asthma8 and the editorial by Van Asperen, Mellis and Robertson, Evidence-based asthma management in children-what’s new? 6 The revised treatment guidelines will provide an opportunity for further education on evidence-based management of asthma in children in 2014 which the NAC is now planning. The guidelines will also be used in other education of primary care health professionals and applied by asthma speciality nurses, asthma educators, clinical nurse consultants, practice nurses, nurse practitioners, GPs and pharmacists, not all prescribers but each with practical influence.

References

1. Roydhouse JK, Shah S, Toelle BG et al. A snapshot of general practitioner attitudes, levels of confidence and self-reported paediatric asthma management practice. Aust J Primary Health 2011: 17; 288–93.

2. National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma Management Handbook. Melbourne: National Asthma Council Australia, 2006.

3. Mellis C. Asthma in children. Australian Doctor 14 December 2012.

4. Van Asperen PP. What’s new in the management of asthma in children? Medicine Today 2011; 12(4).

5. Chuang S, Jaffe A. Cost considerations of therapeutic options for children with asthma. Pediatric Drugs 2012; 14: 212–20.

6. Van Asperen PP, Mellis CM, Sly PD et al. Evidence-based asthma management in children-what’s new? Med J Aust 2011; 194: 383–4.

7. Lemanske Jr RF, Mauger DT, Sorkness CA et al. Step-up therapy for children with uncontrolled asthma receiving inhaled corticosteroids. NEJM 2010; 362: 975–85.

8. Shah S, Sawyer SM, Toelle BG et al. Improving paediatric asthma outcomes in primary health care: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust 2011; 195: 405–9.

9. Van Asperen PP, Mellis CM, Sly PD, for the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. The Role of Corticosteroids in the Management of Childhood Asthma. MJA 2010; (accessed Mar 2013)

10. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma in Children 5 Years and Younger. GINA 2009 (accessed Mar 2013).

11. Van Asperen PP. Long-acting beta2 agonists for childhood asthma. Australian Prescriber 2012; 35(4).